Israelis and Palestinians agree on soccer

TEL AVIV, Israel _ With hatred and distrust of each other at an all-time high, Israelis and Palestinians have finally found something they have in common – their love of soccer. But for many, World Cup 2002 means so much more than the games themselves. The breathtaking matches in the Far East have become a form of escape and even a channel of hope for the violence-ridden residents of the Middle East.

Who said Israelis and Palestinians can’t agree on anything?

“I love Brazil,” proclaimed Avi Chavi, 40, from Tel Aviv.

“They are the best,” asserted Ahmad Abed Aziz, 34, from Khan Yunis, in the Gaza Strip, another diehard Brazil supporter, “I’m sure they will win the World Cup.”

For those still looking for a glimmer of hope and connection between these two bitter Middle East rivals, one should look no further than the World Cup fever, which has swept through Israel, the West Bank and Gaza over the past two weeks.

Soccer — which is called football here as it is in Europe — is by far the most popular sport in this region of the world and World Cup 2002, taking place in Japan and South Korea, has fanatics from both sides of this conflict thinking about something else for a change.

“Everybody loves Brazil,” said Andre Leiter, 27, who immigrated to Israel from Rio de Janeiro in September 2000, just days before the breakout of this current intifada. “I’m sure the Arabs do, too. It’s simply the prettiest football there is.”

Indeed all indications show a high affinity of both Israelis and Palestinians to Ronaldo, Rivaldo and friends. But that’s only part of the picture. A recent poll conducted by “Market Watch” revealed that 44 percent of Israelis planned on watching the live broadcasts of the World Cup, including 57 percent of Israeli men.

The interest on the Palestinian side is equally impressive. “I love football. I have to see the games,” said Said Abdullah, 30, from the Sha’ta refugee camp in Gaza, “I can’t go to sleep at night without watching the games.”

A recent poll conducted by “Market Watch” revealed that 44 percent of Israelis planned on watching the live broadcasts of the World Cup, including 57 percent of Israeli men.

The interest on the Palestinian side is equally impressive. “I love football. I have to see the games,” said Said Abdullah, 30, from the Sha’ta refugee camp in Gaza, “I can’t go to sleep at night without watching the games.”

ESCAPE FROM REALITY

But aside from the action on the field, many here feel that this World Cup is different than those in the past. “It’s the only escape we have in this crazy place,” said Chavi, as he filled out his lottery ticket in downtown Tel Aviv.

“In the past, it was just football, but now? Everything is so awful here. One good game and it takes you away from all that, for a couple of hours at least.”

Abdullah seemed to agree that the Mondial, as the World Cup is commonly referred to here, makes things just a tad bit easier. “Life is so hard now,” he said, “Everyone is trying to run away from it a little.”

In a quiet bar on Dizengoff Street in Tel Aviv, Eyal Berry, a 29-year old graduate student, recently watched the Brazil-China game with friends on a large screen.Abdullah seemed to agree that the Mondial, as the World Cup is commonly referred to here, makes things just a tad bit easier. “Life is so hard now,” he said, “Everyone is trying to run away from it a little.”

“It feels like a holiday,” he said, while drinking his beer. “For one month we can stop listening to the news all the time and just watch football.”

Four years ago for the last World Cup tournament the same bar was flooded with tourists, who have all but disappeared from Israel lately. Leiter, sitting nearby, is experiencing his first World Cup outside of his native Brazil and while he misses the “football atmosphere” of his homeland, as he calls it, he too realizes the unique effect these games are having on his adopted home.

“People have something to talk about now besides suicide bombings,” he said, and then exhibited his newly acquired tint of Middle East skepticism by adding, “but that still doesn’t change the way things are.”

LARGE-SCREEN TV AT THE CAMP

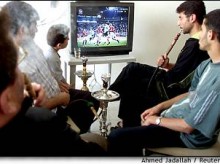

In the Sha’ta refugee camp, many of its 70,000 residents gather around the only large screen TV in the camp and cheer for their favorite teams.

At halftime during a game last week, some of the spectators tried to change channels and watch the news for a while, an act that sparked fierce objections from those trying to ignore their surroundings for just a short while.

It seems that Abdullah, Leiter and others in this region would rather argue over why Romario was left off the Brazilian squad and complain about the difficulty of watching the games during work hours, than deal with the issues they are faced with every day.

But Abed Aziz, like many others, knows that there is a limit to this denial. “Some people are not happy enough to watch the games, they have other things to worry about, like putting food on the table,” he said. “People love football here, but they know that at the end of the game they have to go back to all their troubles.”

For some the escape is more extreme than for others. “Football is a big part of my life,” said Ahmed Hasanin, 28, from Gaza, as he watched Argentina battle England.

Hasanin used to work in Israel and played soccer for a club in Gaza. He has been unemployed for over two years and almost all sporting activities have come to a standstill in Gaza since the beginning of the intifada.

This World Cup has reinvigorated him after many months of isolation in which he spent most of his day sleeping and strolling the streets. He now watches and discusses the games with friends and has found his way of reentered society. “I’ve always been looking for a way to run away from all my problems,” he said. “The football games have given me a chance to do that.”

In Israel, there are similar sentiments.

“Just the other day there was a terrible suicide bombing in the morning,” Chavi said, referring to the deadly blast in Megiddo that killed 17 Israelis. “We live with this all the time. That same afternoon the United States beat Portugal and it was the best match of the tournament so far. After what happened that morning, I needed to go to a place that was fun, a place that was happy. The game took me away from all the terror and death for a little while.”

The games have also had a profound impact on quite a different level. “You see the fans on TV watching football, enjoying the games, leading normal lives, it gives you peace of mind to know that there is a different way to live,” Chavi said.

Berry feels that the World Cup gives people in this region the sense that for once, they are not alone. “We feel like the rest of the world,” he said, “We’re so used to being stuck in the corner all the time. Now all of a sudden we are interested in what is happening outside. We are interested in what the rest of the world is interested in.”

The unusual sense of joy that many are feeling these days has led some to even see sports as a way to bring the two embattled enemies closer together. “There is a camaraderie between football fans all over the world,” Chavi said. “Football can connect people.”

HOPES OF HARMONY

It wouldn’t be the first time soccer has been a bridge.

In May 2000, the Peres Peace Center put together a charity match in Rome between a joint Israeli-Palestinian team and a team of Italian celebrities. Abdullah recalls fondly how four years ago, during the last World Cup, he was in Jaffa, near Tel Aviv, sitting side by side with Israeli friends watching the games in harmony.

“Arabs and Jews, watching together,” he recalled. “There was so much hope. There is no way that could happen today.”

Nevertheless, fans here seem to long for the day when they will not only watch soccer together, but also play it together.

“I hope that one day there will be two teams: Israel and Palestine, and they will play each other in the World Cup,” said Abed Aziz.

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT