Tragedy unites Tel Aviv high school

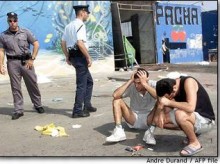

Israeli men cry at the site of a suicide bombing outside a disco in Tel Aviv on June 1, 2001. (AFP photo)

Israeli men cry at the site of a suicide bombing outside a disco in Tel Aviv on June 1, 2001. (AFP photo)

TEL AVIV, Israel — In a society accustomed to grief and tragedy, many Israelis have become inured to the horrors of terror. But the worst terrorist attack in 15 months of Israeli-Palestinian violence devastated Russian immigrants, a community unaccustomed to such bloodshed. More than seven months after the attack, students at a high school that seven of the victims attended are still struggling with their grief — and their identities.

“People here have grown up with a sort of tradition of suffering; when you are an immigrant you don’t have that same connection,” said Simeon Katin, 18, a student at Shevach Moffett High School.

Some believe the aftermath of the June 1 attack at the Dolphinarium Disco — which killed 21 teenagers, all of them immigrants from the former Soviet Union — marked a new willingness by native Israelis to welcome immigrants into the mainstream.

“No doubt about it, the suffering brings people together,” said Katin, who knew many of the victims.

But other students say the attack has only highlighted the divide between native Israelis and immigrants.

A MILLION IMMIGRANTS

More than a million immigrants have arrived in Israel over the past decade, following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Despite the normal initial aches and pains of immigration, the Russian exodus to Israel is viewed largely as an enormous success. Hundreds of thousands of educated scientists, engineers and doctors have joined the civilian and military work force, greatly contributing to the 1990s economic boom in Israel.

Ironically, the tragedy that befell Shevach Moffett has revealed the successes of the immigrant community.

“The story of our school shows the amazing potential of Russian immigration,” said the principal, Dr. Avi Benvenisti.

Ten years ago the school taught professional crafts such as carpentry to 400 Tel Aviv natives and was in danger of being shut down by the Education Ministry. In the years since, the school has undergone an educational and social upheaval as it absorbed new immigrants and shifted the curriculum toward math and science. The school currently has 1,450 students from all over Israel and state-of-the-art laboratories and libraries. It recently won a national education award. “Our school adjusted to the new community, and these kids took a school on the brink of being shut down all the way to an education award,” Benvenisti says.

The students seem equally impressed. “I love this school, I love the atmosphere,” says Katin, whose family arrived from Moscow eight years ago.

His friend Andrei Makarov, whose family arrived seven years ago from a town near Kiev, Ukraine, agrees. He says that he was attracted to the school primarily because of the high academic level. “I’m more comfortable today speaking Hebrew than I am speaking Russian,” he says proudly.

But both acknowledge that sharing a common background with other students, at a school where 95 percent of the students are immigrants, was also important.

“I’m not sure it would be this way at a regular school, with regular Israelis,” says Katin. “It’s a closed school, which makes it hard to integrate into Israeli society, but it’s much more comfortable for the newcomers.”

NOT A MELTING POT

Benvenisti says that schools don’t necessarily have to be melting pots and that absorption is a long procedure. “Our school is a bridge which makes the entry into Israeli society easier.”

All the classes are held in Hebrew, but once the bell rings, the Russian chatter begins. “We’ll be absorbed in the army and in university, but right now, at this stage, I’m better off here,” says Dimitri Bilaous, who arrived in Israel just two years ago from Ukraine. “There’s just a different feeling at this school. I don’t feel like a foreigner in Israel, but I don’t quite feel like everyone else yet either.”

Everyone felt different on that fateful Friday night in June, when an Islamic militant walked into the packed crowd waiting to enter the beachside disco and detonated a bomb he was carrying.

Shevach Moffett was stunned as seven of its students were killed and dozens injured.

“It was very hard, we had never encountered anything like it,” said Katin, who was in the midst of planning a year-end party at the same disco.

As luck would have it, Katin was not there the night of the attack. “You’re not used to losing friends at age 17” he said.

Student Mali Cherniakov was 7 years old when her family arrived in Israel. Now 18, she speaks impeccable, unaccented Hebrew.

She worked for the disco and narrowly avoided death herself. She acknowledges that although what happened that night was out of her control, her conscience wasn’t clear. “Some of the people I invited were hurt,” she says. “I feel that I still haven’t completely grasped what happened that night.”

ANOTHER BLOW

The attack and its aftermath exposed the Russian community in general — and the school in particular — to the vast Israeli public, which is often unaware of the presence and impact of Russian immigrants.

The immigrant community seized the nation’s attention once again in early October when a passenger plane traveling from Israel to Siberia was mistakenly shot down by a stray Ukrainian missile over the Black Sea, killing all 77 passengers on board.

DISRESPECT TOWARD RUSSIANS?

Makarov and many of his classmates have said the bombing hurt everyone, not just Russians. But not everyone agrees.

“I feel that there is disrespect in the public towards the Russian victims,” said 17-year-old Yuri Sheplenko. “Besides the school, nobody cares about the victims,” he said, adding that he believes the state of Israel places greater value on the lives of Israeli natives than on those of immigrants.

His classmate, Katia Sokolovski, also 17, said that following both tragedies she heard her mother blurt out in frustration, “Why did we come here? To have our children killed?”

Benvenisti points to the difference in views as evidence of the heterogeneous nature of the Russian immigrant community now. “They are a part of Israeli society,” he says, “which means that they are part of the happy things and the sad things.”

Most students seemed to agree, but some differed on the implications of the attack for their absorption into Israeli society.

Simeon said he was moved by the enormous support the school received from the public at large and pointed out that the ensuing exposure highlighted his community’s great contribution to Israeli society.

But Mali Cherniakov said it shouldn’t have taken a terrorist attack for immigrants to receive such attention.

“We don’t have to die,” she said sadly, “to prove that we are Israelis.”

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT