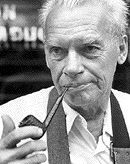

Ottawa photographer Andy Andrews dies at 83

Many Ottawans may not remember the name Andy Andrews, but few can forget the images he left behind.

Over the course of six decades, if there was something significant happening in Ottawa, Mr. Andrews would be there, pipe in mouth and camera in hand, recording history.

He was a fixture in the Ottawa photography community. From his historic pictures of Elvis Presley’s visit in 1957, to his landmark photo shop in the Sparks Street mall, to the tens of thousands of his negatives that live on in the City of Ottawa Archives, Mr. Andrews — through his pictures — paved the way for a generation of photographers.

On Dec. 31, he died after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease. He was 83 years old.

Albert Cole Andrews was born in 1921 in Haileybury, but was known throughout his life simply as Andy. As a young boy growing up in Cobalt and Kirkland Lake in Northern Ontario, he followed in his father’s footsteps, taking a keen interest in photography that would last his entire life.

He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and taught airframe mechanics in St. Thomas, Ont. During the Second World War, he served as a navigator with the Ferry Command, flying countless missions over Europe and the Far East.

Even in wartime, he couldn’t forget his great passion.

“He snuck a camera on board the bombers that he flew. He buried it in his flying suit,” recalled his son, David Andrews. “We’ve got tons of the albums from those photos.”

After the war, he settled in Ottawa with wife Jean Markell. The couple had two children, David and Laurie.

Throughout his long career, he combined photojournalism with commercial and industrial photography, equally at ease capturing a fire or a fair, a politician or a party.

He opened the Andrews Art Shoppe at Carling and Bronson avenues. In the early ’50s, he joined Newton Photographic and spent many years providing news photographs for the Citizen.

Later, he started Andrews-Hunt Photography, before co-owning and operating Andrews-Newton Photography.

He was the official photographer of the Central Canada Exhibition and won numerous awards.

“He covered everything from the construction of the Ottawa sewers to the home of the Governor General. That was the full gamut of what we did,” said Greg Newton, his partner of 20 years. “Through all that time we never had an argument.”

In 1965, Mr. Andrews hired Rod MacIvor, who was fresh out of high school, to his first job in photography. He became his mentor.

“He treated me like a son,” said Mr. MacIvor, now a Citizen photographer entering his 40th year in the business. “He decided, ‘I’m going to help this kid.’ You don’t find many people like that.”

Mr. MacIvor credits Mr. Andrews with teaching him “the business,” and for “giving me the skills I needed to survive later in life.”

He said Mr. Andrews was the quintessential laid-back photographer.

“He was never in a hurry. Everything was stress-free,” he said. “He was a very relaxed, happy, smiling, pipe-smoking photographer. Everyone knew Andy by his pipe.”

Aside from the trademark pipe, Mr. Andrews was also known for his camera giving preference to no one.

“I learned from him that all people are equally important, whether it’s the prime minister, or someone getting their passport picture, of someone at their wedding,” said Mr. MacIvor.

David Andrews is a third-generation photographer. He worked with his father for 18 years before moving on to specialize in digital images. He said his father was a modest man and will be remembered most for his generosity and friendship.

“He helped out a lot of people. He gave people jobs. He let them into his home. The front door was always open. He wouldn’t say much, but people were always welcome,” he said.

While Mr. Andrews was an extremely private man, he touched many people with his art.

“Dad was not a real talker,” he said. But “he could take a very sensitive picture. I think the camera was clearly his means of expression.”

Mr. Andrews suffered a major stroke in 1996. He was later stricken with several smaller strokes and by Alzheimer’s. He had lived in a nursing home the past seven years.

In the last few years, he no longer was able to recognize his own children.

His painful last years, though, did nothing to diminish his legacy.

“For me, he gave me a love of the still image,” said his son.

“I got to know him as a dad, of course. But I got a glimpse of his world, and it gave me a glimpse of the power of the still image and the feelings that are in them.”

Mr. Andrews is survived by his wife and two children, as well as five grandchildren.

Contact aron

Contact aron RSS SUBSCRIBE

RSS SUBSCRIBE ALERT

ALERT